On the surface, it would seem appropriate to compare videogames to movies. Certainly, big budget videogames have often put on the appearance of being like blockbuster films. From the badly compressed and poorly acted Full Motion Video (FMV) cutscenes in Sega CD games like Sewer Shark and Night Trap to the recycled Hollywood action of the Call of Duty series, AAA games invoke the techniques and tropes of mainstream cinema. Of course, the main problem with many of these games is that they fail to effectively adapt the techniques of film to the game environment. They never explore what each medium has to offer the other.

Virginia, a narrative videogame about two FBI agents investigating the mysterious disappearance of a boy in the early 1990s, is one of the few videogames I have played that successfully navigates the impasse between games and cinema. Furthermore, it adapts an underlying principle of film that all cinema-inflected and narratively driven videogames should adopt.

So often when discussing what makes a “good” videogame buzzwords like interactivity, immersion, and emergence are used. These principles are often presented as the holy trinity of good game design. All videogames should be easy to learn and hard to master, so we’re told, and these three principles are the way to get there. A good videogame should privilege the ability of the player to interact and move about in the gameworld, it should have the player become totally immersed in the gameplay, and furthermore the player should be able to find emergent strategies while playing to hit the sweet spot between challenge and fun. It may be surprising then that Virginia is a great videogame that does not respect any of these principles.

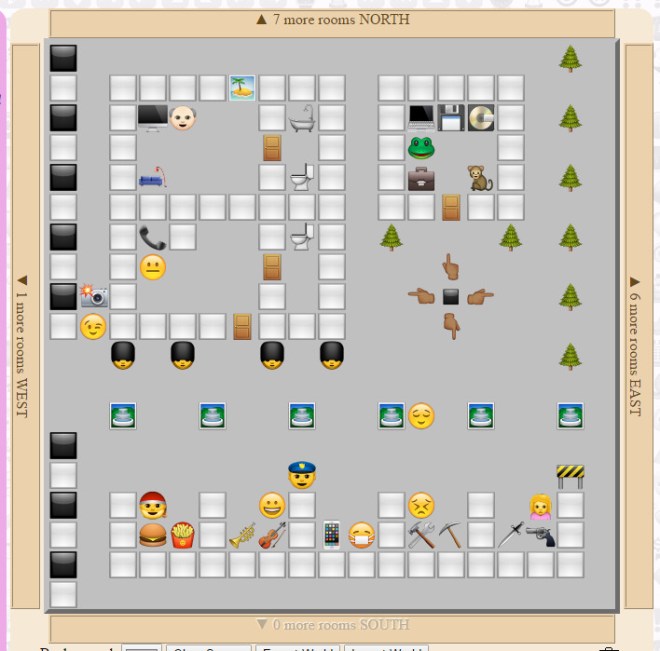

The level of interaction is very limited. Each scene in the game has very few items you can touch and use, and these are often made quite obvious to you. The gameworld is beautiful and engaging but generally not immersive in the way videogames are supposed to be. Cinematic editing techniques like match cuts and dissolves transport you from scene to scene, preventing you from lingering too long at any point while playing. Finally, the game can be finished in about 90 minutes to two hours and is easy to play. There are no emergent strategies or mastery involved. It provides you with a very focused and specific experience, and then it’s over.

So why do I think Virginia is a great game? I argue it’s because Virginia adapts a particular principle from film that makes it successful in keeping the player engaged with its story and gameworld. That principle is framing, which can be defined as the particular composition of the visual elements in a scene. Virginia does this masterfully, as every scene is well composed and visually coherent, even though you essentially act as the game’s camera. The player experiences the entire game from the first-person point of view as FBI special agent Anne Tarver. The game never breaks this point of view, having you experience everything from basic interactions (like shaking someone’s hand or picking up an object) to your brief encounters with text (such as quickly reading a file on a computer screen) entirely from Anne’s eyes.

You play the entire game from the viewpoint of FBI Special Agent Anne Tarver.

Throughout the game, you feel like you’re moving Anne and a movie camera at the same time, but it’s never confusing or incoherent. This is because Virginia’s directors, Jonathan Burroughs and Terry Kenny, ensure that their use of framing is gamelike and dynamic. The game directors bring together strong visual composition with playful movement by:

- giving the player a very specific point of view (FBI Special Agent Anne Tarver) and using that for strong characterization and narrative depth;

- avoiding extraneous, unnecessary information or activity (hence the very specific forms of interaction)

- ensuring the experience is contained within a specific point of time and is not padded out for the sake of increased playtime (the game can be completed in about two hours and you are often moved from scene to scene without too much time passing); and

- providing the player with a clear path to navigate the story and gameworld.

Another reason for the game’s unusually strong scenic composition is that there is not a single line of spoken dialogue. The entire story is told through animation, music, your interaction with the gameworld, and the repeated use of specific images and symbols. Certain motifs such as sitting in the passenger seat of a car with your FBI partner Maria Halperin, holding a dead cardinal, being confronted by a bison, seeing a mysterious red door, or looking down at a broken key, recur often, giving vital clues to unlocking the story.

The appearance of a bison is a recurring visual motif throughout Virginia

These recurring visual motifs are necessary as the game’s narrative has quite a bit of depth. The story of Virginia is one professional betrayal, conspiracy, cult activity, departmental corruption, and even gender and racial discrimination. It also relates many of these events in non-chronological order, while blending together fantasy and reality (mostly in the form of dream sequences). That Virginia can handle these themes and story-telling techniques deftly and subtly without dialogue is a testament to how well it uses framing to anchor the whole experience. While the makers of Virginia have mentioned ‘90s cult TV shows like Twin Peaks, The X-Files, and The Outer Limits as inspirations, they’re able to create their own visual language that is not just a pastiche of these influences.

To reiterate, the principle of framing, especially in the videogame context, requires strong visualization, coherent action, a specific time frame, and finally clear navigation through the gameworld. This ensures you can combine filmic techniques with gamelike elements to tell an interesting, compelling story. The lack of good framing is why I think games like Konami’s Metal Gear Solid series— which certainly has cinematic ambitions —fail to combine games and films effectively. Although Metal Gear Solid game director Hideo Kojima’s fourth-wall breaking and detached irony are amusing, it must be admitted that his games are overly expository, narratively confusing, and quite visually jumbled, even if they offer fun stealth action.

I also want my concept of framing to stand in contrast to Ian Bogost’s concept of proceduralism. In the “Art” chapter of How To Do Things With Videogames he uses this term to describe one way of understanding the games of designers Jason Rohrer and Jonathan Blow. He writes:

“…proceduralist games are process intensive-they rely primarily on computational rules to produce their artistic meaning. In these games, expression arises primarily from the player’s interaction with the game’s mechanics and dynamics, and less so (in some cases almost not at all) in their visual, aural, and textual aspects.” (Bogost 2011, p.13)

Bogost argues that proceduralist games reveal the form of a game in order to have “meaning emanate from the model.” (Bogost 2011, p.13) My account of framing is different in that the visual, aural, and textual aspects are made central to communicating the game’s meaning. I’m not against Bogost’s concept as it may apply to games like Passage and Braid, but rather I am trying to provide another way of thinking about how a game can convey itself meaningfully to the player.

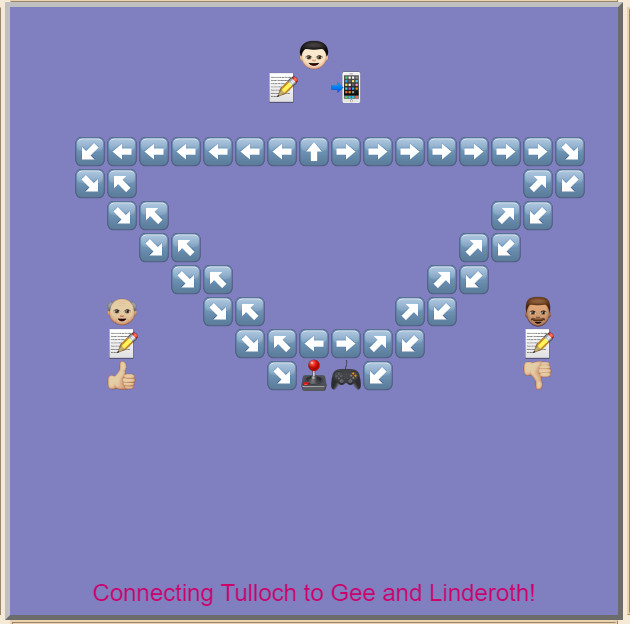

Studying the visual coherence that a game brings to each scene, and how it handles player visuals and movement is an important and overlooked aspect of games criticism. While games critics tend to gravitate toward whether a game is sufficiently interactive or challenging, the actual composition of each scene of game, whether it is experienced from the point of the view of the player or through a cutscene, is ignored. Framing is a valuable tool for thinking about strong visual storytelling in games, and can help critics discern those games that successfully adapt techniques from a medium like film to tell interesting stories.

One of the many times you’re in the passenger seat with your partner Maria Halperin

References

Bogost, I. (2011). How to do things with videogames. University of Minnesota Press.

Variable State Ltd. (2016). Virginia.